Forgotten Colors

by Philipp Hindahl

Trees in Poland, snow outside Stalingrad, the North African desert, they all have their individual colors. Their shades and hues do not change, probably not even over the course of decades or centuries yet the collective memory of succeeding generations recalls the sites of World War II almost exclusively in black and white. When we are shown colour images from the war, the effect is a peculiar one: They almost seem too real, as though something had been added to the document, the photograph, the film, like an illicit increase in realism. There are

also those colors, however, that have been lost or forgotten. Camouflage colors, standardised colors, industrially produced varnishes. They appear and then disappear again. It would almost be possible to write a history of the twentieth century on the basis of colors and varnishes alone.

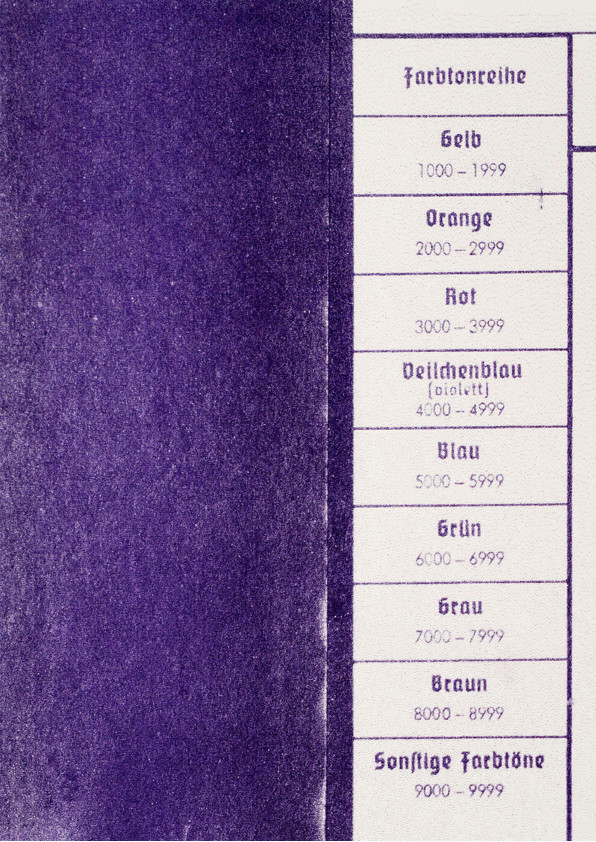

One of the great fears of modernity is the standardisation of all areas of life. At the same time, that fear is a promise: Everything is supposed to be reproducible everywhere, in consistent quality. Whenever utility objects are manufactured industrially, standards are a necessity. This also applies to the colors used for varnishing, painting and dying utility products. In 1925 a joint initiative between government and private industry saw the establishment of the Reichsausschuss für Lieferbedingungen (Reich Committee for Delivery Regulations), shortened to RAL in accordance with the time’s fondness for abbreviations. Here too, standardisation was a driving force: Two years later, the RAL would go on to define forty standard colors.

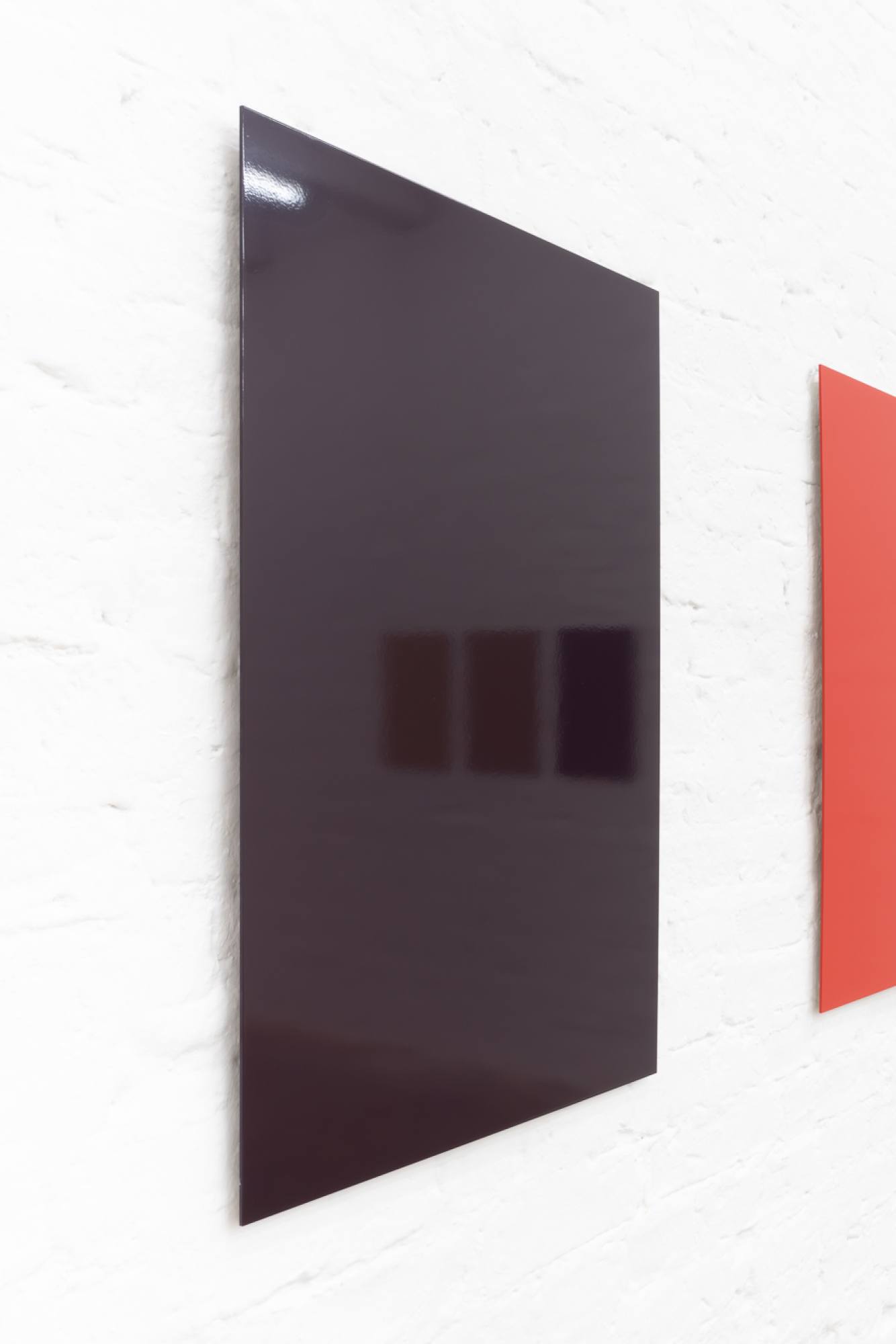

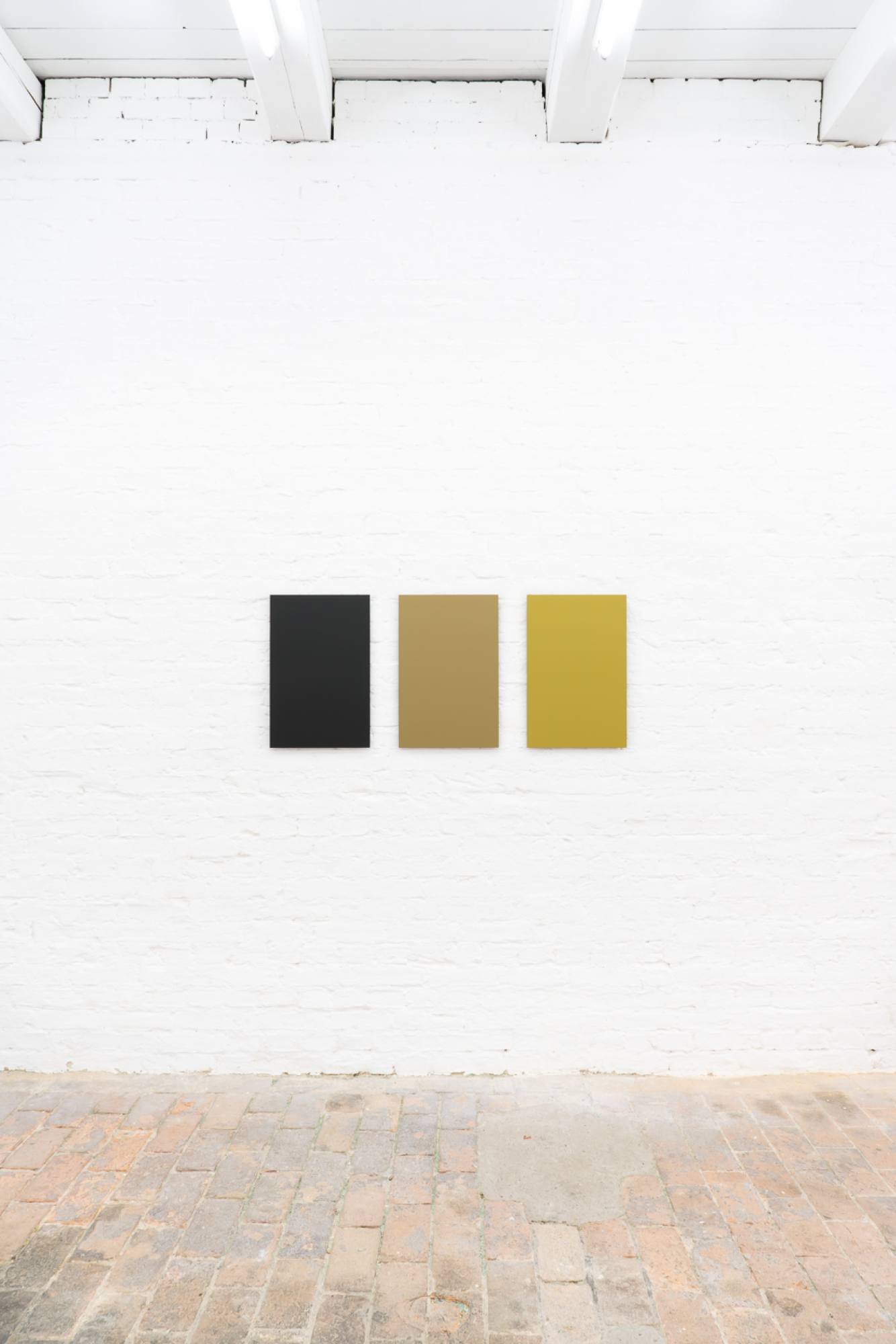

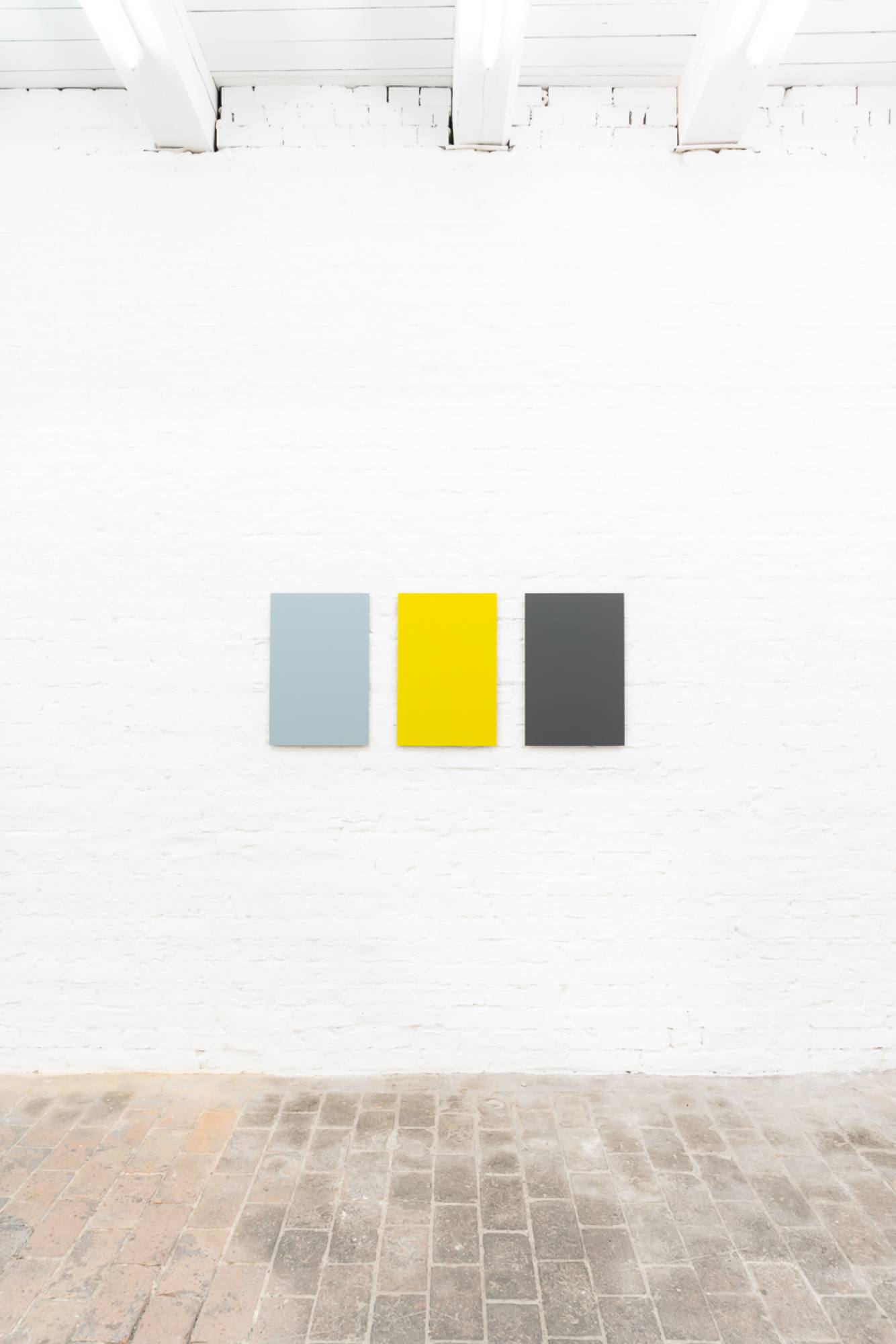

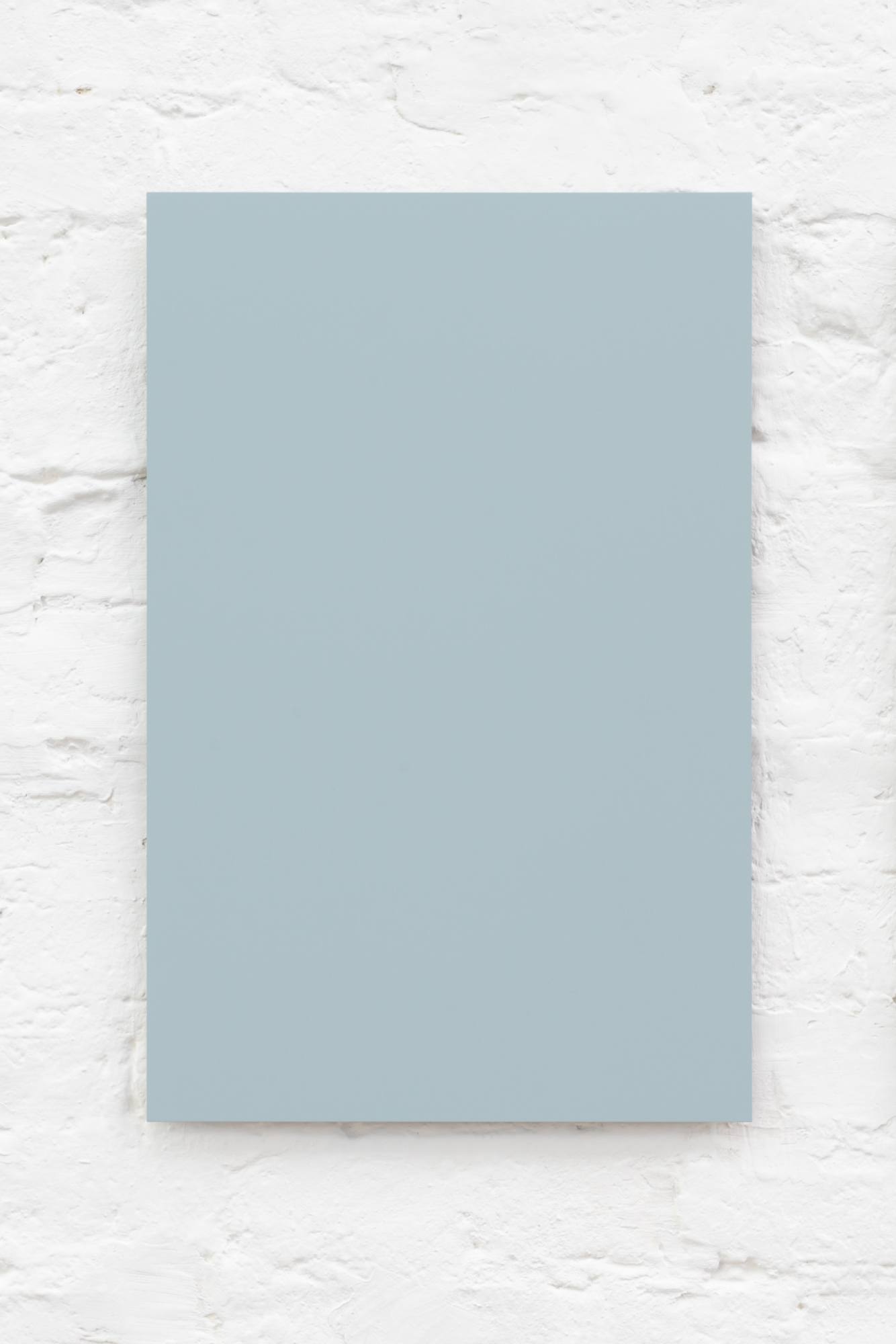

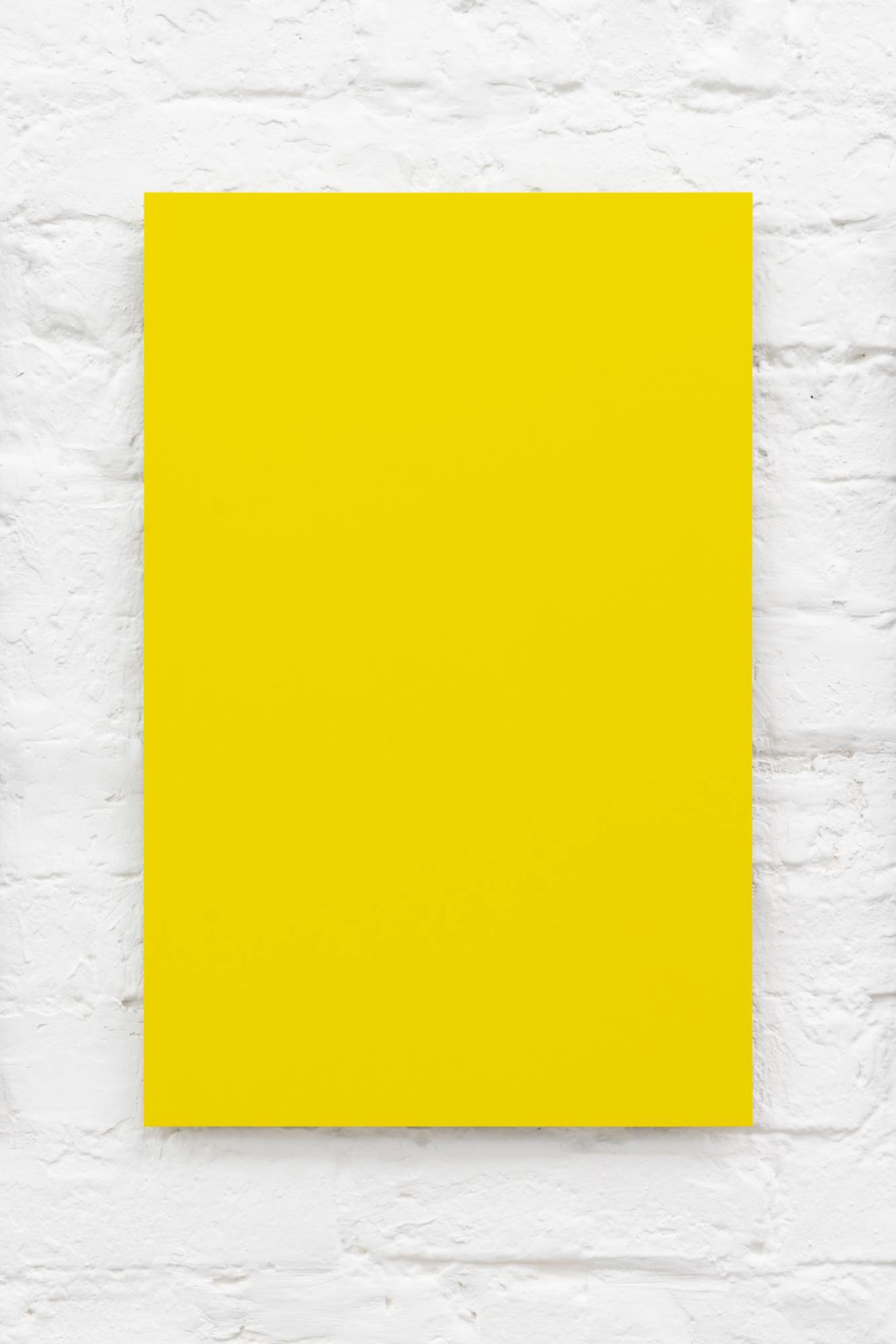

RAL is not a classification system like the Pantone Rainbow but a collection of colors still in use to this day. What fascinates Carsten Becker are the gaps in this collection: Few things have more to say than that which is concealed and lost. For instance, Becker uses panzer grey,

sand grey and dark yellow to produce triptychs. His intensive working of the RAL colors also serves to reveal the subtle changes between seemingly identical hues.

In 1932, an updated version of the RAL color collection was published. The coloring standard applies to industry, the railroad and the military. Not only government bodies – such as the Reichsbahn, the German State Railroad – were among the subscribers to the color collection, but a political party as well: the NSDAP. The idea of uniformity was not a Nazi invention, but it meshed perfectly with fascist cultural policy. Under national socialist rule, norms became duty, and the shapes and hues of utility objects became political.

Becker’s triptychs tell a story, but in abstract fashion: They gather monochrome panels of RAL colors, most of which are thematically connected. The coating varnish of the Messerschmitt BF 109, for instance: light grey underneath, so as to be camouflaged against

the sky, green grey on top to merge with the ground. The nose of the fighter jet is painted yellow – a striking colour used to identify friend or foe. These three colors form a triptych. Or the three colors of the Reichsbahn: Violet for the luxury waggons, flame red for the wheels

and red brown for the box waggons. RAL 8012, the varnish used on the box waggons in which people were transported to concentration camps, bears witness to the Shoa. A waggon of this kind can still be seen today at the holocaust memorial of Yad Vashem.

The history of RAL does not end with World War II. Many colors were renamed or simply taken out of the collection. The denazification of the post-war years was also to affect the symbolic world of color standards.

Many colors are embedded in cultural memory. The leading medium of television archives the early 1970s in color, for example the manhunt for the terrorists of the RAF (Red Army Fraction). When Andreas Baader is captured in Frankfurt in 1972, the police are wearing fir green uniforms. Succeeding generations know the police in mint green; from 2004 onwards, uniforms and vehicles change their color to traffic blue.

The camouflage paints employed by the Bundeswehr (Federal Armed Forces) are called tar black, leather brown or bronze green. The colors bear names that recall a pre-industrial world. In the 1960s, the FeTAp 611 telephones of the Bundespost (Federal Post Office) are made from pebble grey ABS plastic. Since 1986, the Deutsche Post is colored in broom yellow. Only the name telemagenta, a permanent feature in the design of Telekom, belongs to the initial era of digital communication.

Colors for camouflage, for identifiation, for standardised design: Focusing on these alone, a story can be told about the corporate design of German Fascism. The history of the Federal Republic is accompanied by RAL colors. Like a microcosm, the color collection contains a miniature reflection of historical events.

Translation: Philipp Multhaupt

Related Link: Carsten Becker